Figures can't lie...

July's economic date was good, bad and puzzling.

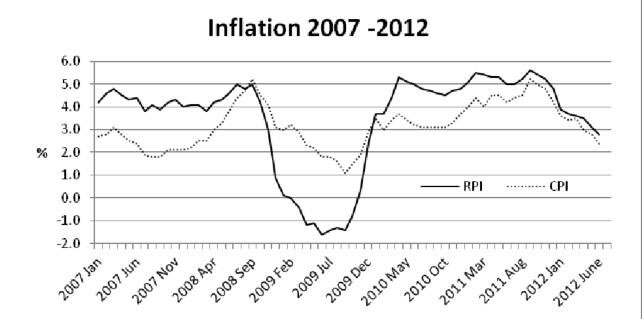

First, the good news: the latest inflation figures (for June) showed a surprisingly large fall. The Government's favoured measure of inflation, the Consumer Prices Index (CPI), is now running at 2.4%, while the Retail Prices Index (RPI) is 2.8%. As the graph shows, the fall in inflation since last September's peak has been dramatic.

The decline has been assisted by the January 2011 VAT increase falling out of the yearly comparison, but there are other factors at work. For example, an early start in June to the summer sales may have helped bring down prices. The fall in inflation ought to give some support to consumers, because it narrows the gap between inflation and wage increases (1.5% including bonuses, at last count).

There was also good news on the employment front, where the number of unemployed fell by 65,000 over the March-May quarter (to 2.58 million) and the overall number employed increased by 181,000 across the same period.

The bad news, which followed the two slices of good news, was seriously bad: the Office for National Statistics' (ONS's) preliminary estimate was that the UK economy shrank by 0.7% in the second quarter – the third successive decline. The pundits had been expecting a fall – all those Bank Holidays in June – but their consensus was -0.2%. If the ONS figure is proved right (it will be regularly reviewed as more data emerges) then UK plc is 0.8% smaller than it was a year ago and 4.5% below its size in the first quarter of 2008.

For investors this data trio raises a number of questions:

a) Are the GDP and employment numbers both correct?

b) If they are, why is employment rising at the same time as the economy is contracting?

c) If they are not correct, which one is wrong, or are they both incorrect?

d) With inflation now heading towards its 2% target, will the Bank of England take any further action to boost demand?

e) What will the Chancellor do? There is growing pressure for a 'Plan B' alternative to Plan A's unrelenting austerity. The autumn statement, when the Office for Budget Responsibility updates its projections, promises to be a challenge for Mr Osborne.

Meanwhile, just to add to the confusion, late July's pre-Olympics surge of company results pointed to the corporate sector being in reasonable health.

The value of your investment can go down as well as up and you may not get back the full amount you invested. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Investing in shares should be regarded as a long-term investment and should fit in with your overall attitude to risk and financial circumstances.

Of less than no interest

Some investors are now accepting negative interest rates.

While much of the media attention has been on the high rates of interest that Spain and Italy are suffering, at the other end of Europe some countries are now paying negative interest. Germany, the Netherlands and Denmark have now been dubbed 'Club Neg' (a play on the so-called 'Club Med' problem economies of Spain, Greece, Italy and Portugal). Last month Germany sold two-year government bonds that were offering investors a return of -0.06%.

There are three main reasons why investors are willing to pay rather than earn interest:

a) In July the European Central Bank (ECB) reduced to nil the interest it offered on deposits received from commercial banks. The aim was to encourage banks to put their money elsewhere.

b) The problems in the Club Med group have driven many of their wealthier residents and other euroinvestors to seek safety, rather than yield. As several commentators have remarked, return of capital has become more important than return on capital.

c) There is a shortage of top-quality secure assets, such as short-term bonds from AAA-rated issuers (e.g. Germany). Supply is being outstripped by demand, which has been exacerbated by the ECB's zerointerest policy.

Negative interest rates are nothing new, but in the past they have usually been associated with short-term actions by countries trying to stop speculative inflows of 'hot money' – Switzerland being a classic example. This time around it looks as if negative rates will not be disappearing quickly. Indeed, there is a possibility of them spreading further: there have been calls for both the Bank of England and the US Federal Reserve to follow the ECB's lead. We do not have far to go – the UK's two-year gilts yield just 0.1%.

That holiday feeling

Foreign currencies are not only for holidays.

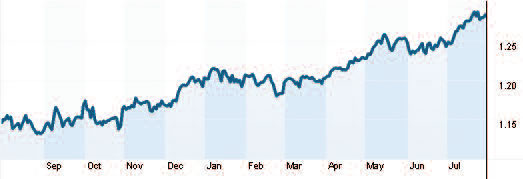

If you are off to the Mediterranean this summer, you should find it usefully cheaper than a year ago. At the beginning of August 2011 £1 was worth €1.145 on the foreign exchange markets, whereas today it buys around €1.28, meaning euro prices have fallen by about 10% in sterling terms. While there has been a year's inflation to counter the euro's depreciation, price increases are running at an annual 2.4% in the Eurozone as a whole, under 2% in Spain and below 1% in Greece.

The quid pro quo for the cold beer being cheaper is that investments in euro-denominated assets – be they shares, villas or bonds – are worth less in sterling terms, before any market movements are taken into account. The same does not necessarily apply to funds investing in the Eurozone. Some fund managers will have hedged their currency exposure, fearing a decline in the euro, whereas others never try to second guess the foreign exchange market. Who does what and when is not always obvious – if you want to know more, please ask us.

The value of your investment can go down as well as up and you may not get back the full amount you invested. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Investing in shares should be regarded as a long-term investment and should fit in with your overall attitude to risk and financial circumstances. For funds that invest overseas, the return may increase or decrease as a result of currency fluctuations.

Income drawdown rates reach their floor

The rates for income drawdown reached a new low this month.

Income drawdown – drawing an income directly from your pension plan – has been a popular alternative to buying an annuity for some years. However, because of the risks involved in drawdown, normally the option should only be considered if you have other reliable sources of retirement income.

One of those risks is that the maximum amount that you can withdraw will fall when the plan is reviewed (now on a three-year cycle up to age 75 and yearly thereafter). Reviews falling due this month will be based on the lowest drawdown rates ever, a reflection of the historically low yields on gilts. To make matters worse, those reviews will normally be for plans which had previously used a different, more generous basis for setting drawdown limits and a five-year review period. The effect can be dramatic: for a man aged 60 in August 2007, the maximum withdrawal rate was £82.80 per £1,000 of fund. Now five years older, the same theoretical man's maximum has dropped to £53 per £1,000. And that is before you consider what has happened to the underlying investments since 2007…

One small crumb of good news is that the drawdown rates cannot drop further: they have now reached the floor set by HMRC earlier this year. The fall in drawdown limits largely echoes the decline in annuity rates, so the relative merits and demerits of the two income routes remain similar. However, for technical reasons the top annuity rates are up to 20% higher than the maximum drawdown rates.

The value of your investment can go down as well as up and you may not get back the full amount you invested. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

Long-term care heads back to the long grass…

The Government has delayed decisions on long-term care.

How to deal with the provision of long-term care for an ageing population is an issue which seems to generate government reports rather than government action.

In 1999 there was a Royal Commission investigation and this has been followed by a variety of other reviews. The coalition Government set up its own commission, shortly after coming into power. It was chaired by Andrew Dilnot, a former head of the Institute of Fiscal Studies, who issued his report in July 2011. The Government response was originally due to coincide with this year's Budget, but in the event a White Paper finally emerged from the Department for Health in July, to a chorus of raspberries.

The Health Secretary said that he agreed with the principles set out by the Dilnot Commission for dealing with long-term care in England, but then sidestepped three crucial issues:

a) What will be the basis of a new means test for assessing personal contribution levels?

b) What will be the amount of the cap on total personal payments for care? And

c) How will any new system be funded?

We now have to wait for the next government spending review (due in late 2013) before answers begin to emerge, so reform is unlikely to occur before the next election.

All of this means that if you need to look at financing long-term care – either now or in the next few years (and perhaps for an elderly relative) – you must take expert advice to ensure that any plan has sufficient flexibility. A rest-of-life solution, such as a long-term care annuity, could well be a waste of money.