The UK economy picks up

The latest figures for the UK economy show that growth is returning, but there is a long way to go

Cast your mind back a little over three months to late April. It was still winter and there was a distinct possibility that the preliminary UK Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for the first three months of 2013 would show the economy shrinking for a second successive quarter, creating a “triple dip” recession. However, the GDP figures issued by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) on 25 April confounded the pessimists and showed growth of 0.3%.

Two months later, the ONS revised some 2012 statistics, stating that the first quarter of last year had seen no growth, rather than the 0.1% contraction of previous calculations. That meant there were not the two consecutive quarters of shrinkage that are the ingredients of a recession, and hence even the “double dip” recession also disappeared.

In July there was a third round of good news, with preliminary figures for the second quarter suggesting that the UK economy had grown by 0.6%. This was faster than the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) was expecting and points to a rarity in future OBR forecasts; an upgrading to growth numbers.

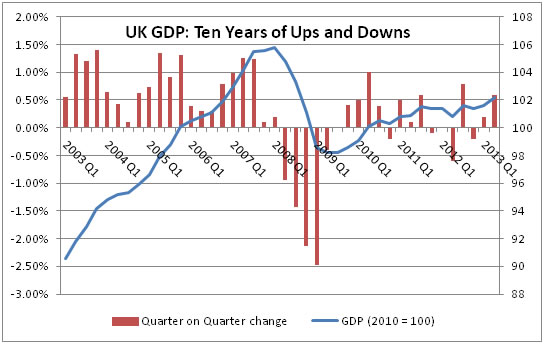

These signs indicate an economy on the mend, but there is a long way to go. As the graph below shows, the overall output of UK plc is still over 3% below the peak set in the first quarter of 2008 and at much the same level as at the end of 2006.

The gap between where we are now and where we might have been in the GDP growth line before the financial crisis in 2008, is one measure of how much the downturn has cost the economy. On a more optimistic note, it also suggests plenty of scope for future growth.

Unfair dismissals awards revised

When employees are unfairly dismissed, they are entitled to a basic award and an employment tribunal may also award a compensation.

The basic award is straightforward enough: it is calculated in a similar way to a statutory redundancy payment, taking into account the employee’s age, length of service and weekly pay.

The compensatory award is more subjective. This is an amount set by the tribunal based on factors such as the employee’s loss of earnings up to the date of the tribunal (taking account of any new employment), loss of future earnings (again taking account of any new employment), loss of associated benefits (such as a company car or medical coverage) and the loss of pension rights.

In the present recession, it can take much longer to find new employment with equivalent pay and status, so not surprisingly tribunals have sometimes based compensatory awards on more than 12 months of lost future earnings. The only restriction currently is a statutory cap of £74,200 (which is revised in February each year). However, once draft legislation is enacted, compensatory awards will in future be capped at the lower of £74,200 and 52 weeks’ pay – and it will apply to such cases where employment is terminated after the date of enactment.

Most people earn well below £74,200, so in theory they could currently be awarded much more than one year’s salary as compensation, especially if the award includes loss of benefits and pension rights. In future, employers could therefore in some instances benefit by being subject to lower awards than at present. For example, an employee on an annual salary of £45,000 could previously have been awarded up to £74,200, but the new maximum for them will be £45,000.

However in most cases, the new limit will not make any difference because only a very small proportion of awards exceed £50,000. Also, some unfair dismissals are not subject to any cap, including cases of discrimination and whistle-blowing dismissals.

Not-so-premium bond

National Savings & Investments are cutting the prize money on premium bonds.

In June, National Savings & Investments (NS&I) announced reductions of between 0.4% and 0.5% from 12 September on three of its variable rate offerings, the most significant being a cut in the Income Bond rate from 1.75% to 1.25%. At the time, some of the press coverage commented that the move increased the relative appeal of premium bonds, where the underlying prize money equated to 1.5% tax-free interest.

Last month NS&I reacted to the resultant inflows into premium bonds by cutting the prize money rate to 1.3% from 1 August. The lower rate will result in two changes:

- The chances of any one bond winning a prize in the monthly draw will fall from 1:24,000 to 1:26,000.

- The distribution of winnings will alter (see chart), with an even higher proportion (98.1%) of successful bonds earning their owners the minimum prize of £25.

1.3% tax-free doesn’t look bad if you are a higher rate taxpayer – you would have to earn 2.17% gross interest to match it, which beats any instant access account currently available. However, the 1.3% is theoretical and what you would actually earn depends upon lady luck. The statisticians say that the skew of prizes and the minimum of £25 means on average you will earn less than 1.3%.

Value of prize |

Number of prizes in July 2013 |

Number of prizes in August 2013 (estimate) |

£1,000,000 |

1 |

1 |

£100,000 |

5 |

3 |

£50,000 |

9 |

6 |

£25,000 |

20 |

11 |

£10,000 |

49 |

30 |

£5,000 |

97 |

58 |

£1,000 |

1,142 |

789 |

£500 |

3,426 |

2,367 |

£100 |

33,552 |

11,891 |

£50 |

33,552 |

11,891 |

£25 |

1,831,461 |

1,724,014 |

TOTAL |

1,903,314 |

1,751,061 |

P.S. If you are thinking of that £1 million jackpot, then don’t plan your retirement around it: the odds of winning the top prize in the monthly draw are now less than 1 in 45,500,000,000.

Pensions disappear

The Office for National Statistics has produced a stark picture of the pension landscape.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) regularly examines pension provision in the UK and its data clearly influences government pension policy. Last month the ONS published three revised chapters of its Pension Trends analysis. The underlying research pre-dates the start of auto-enrolment last October and, to some degree, underlines why the government introduced this form of quasi-compulsion to pension provision:

- In 2011 the number of employees accruing pension benefits in occupational pension schemes was 8.2 million, its lowest level since the 1950s. Nearly two thirds of those employees were in the public sector.

- 56% of the employees in private sector final salary schemes were in schemes closed to new entrants.

- 46% of employees were working members of workplace pension schemes in 2012 – the lowest level since these records began in 1997 (at 55%).

- In 2011, 46% of self-employed men had never belonged to a personal pension – the highest level of non-membership since the ONS started collecting data in 1991/92. Just 34% self-employed men belonged to a personal pension in 2011, almost exactly half the proportion recorded in 1991/92.

The decline in private pension provision is hardly news, but the extent of it is a concern. The government’s pension initiatives – auto-enrolment and the new single-tier state pension – are a start, but they are unlikely to be sufficient. The provision you make yourself, whether through additional pension contributions or other retirement savings, will remain an important factor in determining how comfortable your retirement will be.

The value of your investment can go down as well as up and you may not get back the full amount you invested. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

Pension tax relief

Fancy a 30% flat tax relief on your pension contributions?

In 2006 the previous government introduced what it described as ‘pension simplification’, a radical reworking of the pension tax rules. Ever since, there has been a process which has now gained the label of ‘complification’ – adding complexity back into the pension tax system. The current government can take a fair slice of the blame, with its efforts to cut back the cost of tax relief by twice reducing both the lifetime allowance (on total benefits) and the annual allowance (on contributions).

A recent paper from the Pension Policy Institute (PPI) examined who benefits from the current pension regime and highlighted two tax points:

- Basic rate taxpayers are estimated to make 50% of the total pension contributions, but benefit from only 30% of pension tax relief. In contrast, 50% of all pension tax relief goes to higher rate taxpayers, with the balance going to additional rate taxpayers, while these groups make 40% and 10% of the total contributions respectively.

- Currently 77% of pension lump sums by number are under £40,000, but these account for just under a quarter of the tax relief on lump sums. At the opposite end of the scale 2% of lump sums are worth £150,000 or more and they attract nearly a third of tax relief on lump sums.

The PPI’s concluded that instead of marginal rate income tax relief, a flat rate relief of 30% for everyone would be better at incentivising low and middle income earners and spreading the benefit of tax relief more evenly. It looked at a number of options for cutting back on the lump sum, but concluded that these would have limited immediate effect because any change could not be made retrospectively.

The PPI’s ideas on flat rate relief should not be dismissed as just the musings of another think tank. They echo proposals from the Centre for Policy Studies, a think tank founded by Sir Keith Joseph and closely linked to the Conservatives. The other main political parties have both talked about cutting tax relief for high earners, so the writing may well be on the post-election wall.